Journey To The Mountain

"Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!"

I was quite young when I first heard of Mount Saint Helens.

It had erupted four years before I was born; when I first started school, it was still a relatively recent memory, much as 9/11 is still fresh for many of us. Growing up in the house I did, it was the kind of thing I heard about when Dad was watching the Discovery Channel or Mom took us to the library. And being the science geek I've always been, it was the sort of topic I went looking for in said library. I was fascinated by how the eruption had played out, from the studies of the mountain for the weeks prior to the things that had made it so different.

As I got older, I found myself equally fascinated by the scientist that had announced the explosion.

David A. Johnston was 30 years old when the eruption occurred. He was by all accounts a likeable, thorough scientist on the up-and-coming side of things; he was well-respected in his field and particularly interested in the hands-on work that could lead to predicting volcanic eruptions. He believed the risk was worth the potential reward and as such was often among the first to volunteer -- including for the crew that started watching Mount Saint Helens early in 1980. He was also one of the more vehement scientists when it came to keeping the area closed to visitors: he had no doubt an eruption was imminent, and as it was a popular area it was important that people stayed away.

He took a coworker's shift at the Coldwater II post, five miles from the mountain on the north side on May 18th. The mountain had been bulging on that side at an alarming rate and they'd been monitoring it ever since, both the physical dimensions and the gases that were escaping.

When the mountain erupted and the north side gave way in an enormous landslide, Johnston radioed it in -- and then vanished in the blast.

Maybe it was because he was such a normal guy -- not associated with any world-altering theories, not someone who had been in the field for decades -- that I was so fascinated. He had simply been doing his job, one he truly loved and was passionate about.

When I realized I was going to be within a couple hundred miles of the mountain, I knew I had to make the trip.

Fifty miles into Washington on I-5 brings you to the Mount Saint Helens Visitors' Center, still forty miles away from the mountain itself. A stop here yields more information on the geology of the area and the mountain than a person can absorb in a short time; it also gives you your first glance of the mountain, in the form of a webcam at the front desk.

That morning, there were clouds hovering around the crater -- after all, this was Washington in September. But as I'd already come this far, there was no way I wasn't continuing.

Spirit Lake Highway is the lone road open for tourists like me, and it's an absolutely beautiful drive. Fifty miles of winding pavement gradually reveal a landscape still scarred and recovering, from the young trees that were immediately planted (this is a harvest area for Weyerhauser) to the still-not-suitable waters of Spirit Lake itself.

Naturally, I pull off for a bridge -- the Hoffstadt Creek Bridge, a half-mile span fifteen miles from the crater, at the edge of what was hit with the pyroclastic flow.

After this, the mountain itself starts to peek out from time to time. Once the dominant feature on the landscape, it's now around 1,000 feet shorter ... and, well, still a dominant feature.

As you get closer, the landscape gets more and more barren. At first it's only at the bottoms of the valleys, then it slowly spreads up the hillsides. By the time you reach the Johnston Ridge Observatory, you're in land that has only recovered enough for grass to grow.

It's a strikingly beautiful area, the kind that comes with its own eerie stillness. The observatory -- sitting on the ridge that once was called Coldwater II, the very place Johnston died -- features displays focusing on the day itself and the changes on the mountain since then.

Surrounding the area are several paths as well that give you the chance to wander this once-forested land. It's the kind of area that is heavily patrolled -- there is no wandering off the trails -- but still manages to be rather awe-inspiring.

In truth, I'm still not entirely sure what all to say about the area. It was easily the most mind-boggling day I had. Here I was, wandering the site of an event that I'd read about almost since I learned to read, right where a scientist that had played a part in inspiring my own nerdy endeavors had died.

It was gorgeous and sad and thought-provoking all at once. Before I realized it, I had spent over two hours at the observatory -- more than I had really intended -- and it was time for me to continue on my way.

After all, I was headed to the ocean.

I was quite young when I first heard of Mount Saint Helens.

|

| Yes, another bridge. Just a few miles into Washington on I-5. |

As I got older, I found myself equally fascinated by the scientist that had announced the explosion.

|

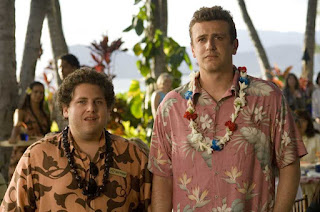

| Johnston at the Coldwater II site a few hours before his death. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia. |

He took a coworker's shift at the Coldwater II post, five miles from the mountain on the north side on May 18th. The mountain had been bulging on that side at an alarming rate and they'd been monitoring it ever since, both the physical dimensions and the gases that were escaping.

When the mountain erupted and the north side gave way in an enormous landslide, Johnston radioed it in -- and then vanished in the blast.

Maybe it was because he was such a normal guy -- not associated with any world-altering theories, not someone who had been in the field for decades -- that I was so fascinated. He had simply been doing his job, one he truly loved and was passionate about.

When I realized I was going to be within a couple hundred miles of the mountain, I knew I had to make the trip.

Fifty miles into Washington on I-5 brings you to the Mount Saint Helens Visitors' Center, still forty miles away from the mountain itself. A stop here yields more information on the geology of the area and the mountain than a person can absorb in a short time; it also gives you your first glance of the mountain, in the form of a webcam at the front desk.

That morning, there were clouds hovering around the crater -- after all, this was Washington in September. But as I'd already come this far, there was no way I wasn't continuing.

Spirit Lake Highway is the lone road open for tourists like me, and it's an absolutely beautiful drive. Fifty miles of winding pavement gradually reveal a landscape still scarred and recovering, from the young trees that were immediately planted (this is a harvest area for Weyerhauser) to the still-not-suitable waters of Spirit Lake itself.

Naturally, I pull off for a bridge -- the Hoffstadt Creek Bridge, a half-mile span fifteen miles from the crater, at the edge of what was hit with the pyroclastic flow.

After this, the mountain itself starts to peek out from time to time. Once the dominant feature on the landscape, it's now around 1,000 feet shorter ... and, well, still a dominant feature.

As you get closer, the landscape gets more and more barren. At first it's only at the bottoms of the valleys, then it slowly spreads up the hillsides. By the time you reach the Johnston Ridge Observatory, you're in land that has only recovered enough for grass to grow.

It's a strikingly beautiful area, the kind that comes with its own eerie stillness. The observatory -- sitting on the ridge that once was called Coldwater II, the very place Johnston died -- features displays focusing on the day itself and the changes on the mountain since then.

Surrounding the area are several paths as well that give you the chance to wander this once-forested land. It's the kind of area that is heavily patrolled -- there is no wandering off the trails -- but still manages to be rather awe-inspiring.

In truth, I'm still not entirely sure what all to say about the area. It was easily the most mind-boggling day I had. Here I was, wandering the site of an event that I'd read about almost since I learned to read, right where a scientist that had played a part in inspiring my own nerdy endeavors had died.

It was gorgeous and sad and thought-provoking all at once. Before I realized it, I had spent over two hours at the observatory -- more than I had really intended -- and it was time for me to continue on my way.

After all, I was headed to the ocean.

Comments